In What Order Should I Start Adding Types?

When we start gradually adopting types in a codebase, whether that’s PHP, Python or JavaScript - there’s a question that pops up. Where do we start adding the types?

When starting out there’s going to be large blocks of code that are virtually impossible to type, with only the information in the codebase.

I’ll present three statements I think are true about the process of adding types, and then suggest an approach for adding types to an existing codebase.

An Example

Let’s view a fictional example written in JavaScript of a function. It boils some water - gets the potId to boil it in and the water from some APIs. It’s a little hard to guess what the different things are, but code is like that sometimes.

function boilWater(){

const water = axios.get("https://somethingFromSomeApi.com/something").data.water

const potIdForWater = axios.get("https://somethingFromSomeOtherApi.com/adress").data.potId

const temperature = getTemperatureToBoilAt();

const heatedWater = getHeatedWater(water, temperature)

sendBoilingWaterToThePot(potIdForWater, heatedWater);

}

In this example, apart from the URL-strings, it’s impossible to type anything from this code. The input from the API could be in any format - there’s certainly no way to tell based on the code. If we wanted to type it, we’d need to record the responses at runtime.

The return values from the API is passed to untyped functions - e.g. they accept arguments of any types. So we also can’t gleam anything of the actual types from what functions they’re passed to.

In general, I think this statement holds true:

“You can’t type things that only reference untyped functions/classes”

If you don’t know what types a function takes, and none of the functions it uses are typed, without runtime analysis, it’s basically impossible to deduct what the types of objects are.

Let’s dive a little deeper into some of the functions of our boilWater example - into the getTemperatureToBoilAt function, which looks like this:

function getTemperatureToBoilAt(){

return "100 celcius";

}

As this is an example, the function is reasonably trivial. This function is very easy to type. It’s completely self contained, it depends on nothing but the built-in language features. It’s easy to tell that this function always returns a string.

This leads me to make the statement:

“Functions that don’t depend on anything but language features are trivial to type.”

Now let’s look at the next function: getHeatedWater

function getHeatedWater(water, temperature) {

// Convert the water to a number

const waterAsNumber = parseInt(water, 10);

// We spilled some..

const remainingWater = waterAsNumber - 10;

// Make sure the temperature is in celcius

if (temperature.indexOf("celcius") == -1){

throw new Error("No imperial units allowed!");

}

return `Heated ${remainingWater} ml water to ${temperature}`;

}

It’s also rather easy to type everything in this function if we’re a little familiar Javascript.

The variable water was a string, as parseInt takes a string and converts it to a number.

The temperature variable must be a string as only strings contain an indexOf method.

Both ways of interacting with the variables reveal the type, but to different degrees.

The first way, using it in a function that is strongly typed, is the strongest.

After seeing the variable get passed to a strongly typed function from the standard-library, and assuming the code has no errors, we’ll know the type of the variable.

The second way, calling a function on the object, gives us a varying amount of information on the type. In our case, we assumed that temperature was a string, as we called indexOf, on it - but Javascripts Array also has an indexOf method. A custom class could also define such a method. From the context it seems obvious we’re not manipulating an array - but can we really tell? Sometimes calling functions on objects are ambiguous - so we might not be able to tell exactly what object it is.

What these two interactions with the objects have in common, is that they both reveal something about the variable, in the first case it’s very unambiguously revealed - ParseInt only takes a String, so water must be a string, but for the second case, all we *really *know is that whatever it is has an indexOf method.

This leads me to the following statement:

“The best place to type variables is somewhere where their type is revealed, preferably in an unambiguous way.”

Let’s have a look at the last function:

function sendBoilingWaterToThePot(potId, heatedWater) {

axios.post(potId, {

water: heatedWater

});

}

In this function, heatedWater could be anything, but axios always takes a string as the url, so we know that the potId must be a string.

This demonstrates that we can also reveal variable types when interacting with third party libraries or our own code - not just the standard-library. Any function that only takes one type of object, will allow us to distinguish the type.

Going back : We now have types for everything, and if we used TypeScript we could type it like this:

function waterBoiler(){

const water: string = axios.get("https://somethingFromSomeApi.com/something").data.water

const potIdForWater: string = axios.get("https://somethingFromSomeOtherApi.com/adress").data.potId

const temperature: string = getTemperatureToBoilAt();

const heatedWater: string = getHeatedWater(water, temperature)

sendBoilingWaterToThePot(potIdForWater, heatedWater);

}

Turns out it’s strings all the way down! It makes the example a little boring, but I think it helps underline the point, that these things can be really hard to properly guess.

Bottom-up type annotations

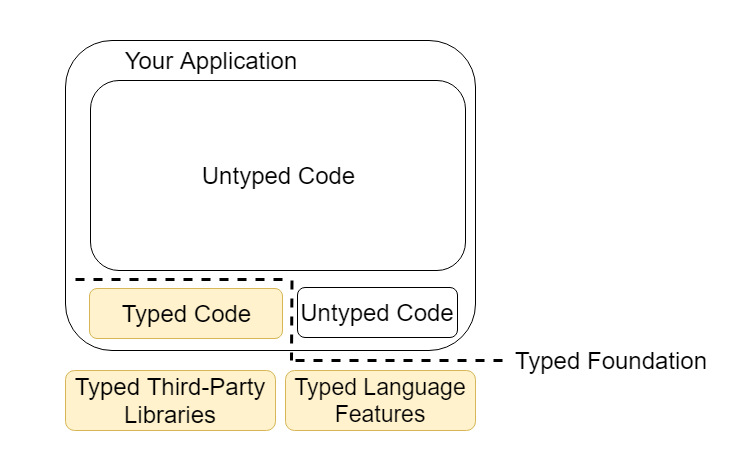

I like to imagine there’s a typed foundation around our code - this foundation is well-typed, we know what types the functions receive, and what types they return. This is the standard-library and well-typed third-party libraries.

Away from the foundation we have *our *code. Some of the code only depend on the typed foundation - as we’ve seen before, this code is easy to type.

When we type this code, it becomes part of the typed foundation - and that in turn makes it possible to add type annotations to the layer on top of it.

When you start typing your code, it becomes part of the typed foundation

When you start typing your code, it becomes part of the typed foundation

As we’ve seen - we might not always have the type information to figure out the types of an arbitrary class in the middle of our application - but there’s always a foundation, and if we focus on expanding that when we add types, the transition is going to be much smoother.

Prime targets for expanding the foundation are files that are imported often, and rely on only the typed foundation. In Javascript you can e.g. use the following python script to see what files are imported the most, and then manually check whether they can be typed.

Did you enjoy this post? Please share it!