4 Future Challenges for TypeScript

Typed Javascript brings a new level of sanity to web development. Better autocomplete, refactoring with a lot more confidence, less bugs - having a typechecker is great. There’s several typed language flavours that transpile to javascript. There’s TypeScript, Flow, Elm, ClojureScript, Reason, Kotlin, etc. Most popular of them, is TypeScript.

While I think TypeScript is great - it’s not all sunshine and rainbows. Here’s the four biggest challenges I see TypeScript facing in the future.

Configuring TypeScript can be overwhelming

All of the compiler flags

This is a general problem in the JavaScript world. Build systems are not easy to figure out for newcomers. Webpack being impossible to configure is a running joke, and there’s also babel - and now TypeScript, which comes with its own setup difficulties.

I think that this labyrinth of complexity is one of the reasons opinionated build tools with no configuration like the angular cli, Create React App, and ParcelJS is gaining momentum.

While TypeScript has some reasonably sane defaults, there’s still (count ‘em) 54 compiler flags in the tsconfig.json file that gets created when setting up a project. Now, most of them have reasonably sane defaults, and a lot of them are added to prevent breaking changes - but after having helped debug my share of faulty tsconfig files, I can tell you people definitely get it wrong.

All 54 of them!

All 54 of them!

Now it’s definitely helped that the tsconfig.json is generated with every flag as a comment, so it’s possible to see what knobs to turn, but it can still be overwhelming to figure out what JavaScript target to use, what module system to use, what libraries to include, etc.

Fitting TypeScript into the JS ecosystem

Now while TypeScript comes with some configuration options, the complexities really start to explode when you want to combine it with the other build tools.

Let’s assume we want to use TypeScript in our webpack build-pipeline. We do that using a loader, but should we use ats or ts-loader? Or should we just run "tsc --watch" and then use the compiled output and feed that into webpack?

Each of the webpack loaders comes with its own set of options. ats has 18 settings and ts-loader has 19 different options.

But perhaps we should not use a TypeScript loader at all? Babel 7 has TypeScript support - it’s still in beta, but a lot of large projects use it already and it seems stable. However the babel TypeScript support is limited in some things you use rarely (const enums and namespaces being the big two) - so is that a tradeoff you’re willing to make for extra simplicity?

@iamdevloper knows how it feels

@iamdevloper knows how it feels

And then you of course need to make it work with your testing framework as well - Jest has ts-jest as a preprocessor for TypeScript, but that also has limitations and some 10-odd configuration options. And you better make sure that it’s configured the same way as your typescript-loader above, or you’ll run into inconsistencies that are very hard to debug.

All of this is perfectly doable, and it doesn’t take me long to set up typescript projects nowadays, but I’ve spent many hours, and I’ve been burned many times to figure out what’s going on. It can definitely be difficult to get started.

Type-system error messages are cryptic

While the TypeScript goal is to type JavaScript as-is, this can be difficult considering how extremely dynamic JavaScript is. A task like that requires a complex type-system as the real life scenarios it has to type are very complex.

The good part is, that the TypeScript type-system is very full-featured, and you can do some amazing things with it.

The bad part is, that when it doesn’t work - it can be absolutely impossible to figure out what the hell is going on. Consider this conversation I had on twitter some time ago:

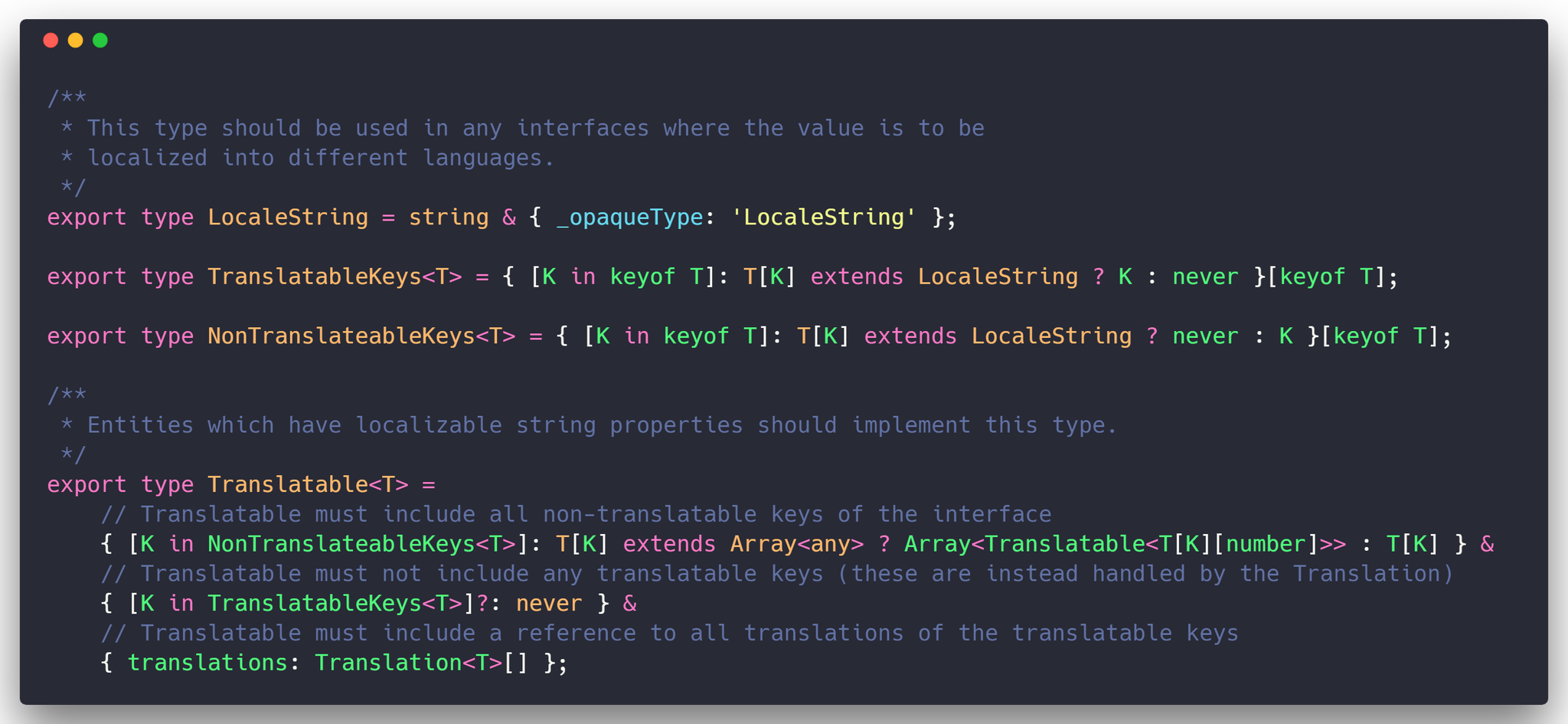

@michlbrmly had done some cool work with conditional types:

The specifics aren’t terribly important, but using some clever type-system magic it defines an object that contain both translate-able and non-translatable key for localization.

The first thing to notice here, is that while these types are very clever - they’re also clever enough that even with comments describing them, I have a hard time figuring what’s going on.

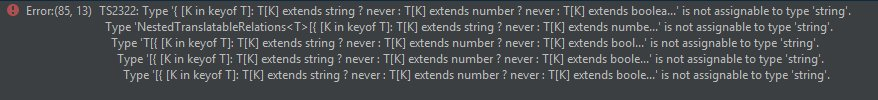

Now, the second problem is - if a library used these typings, and you specified a wrong type. This is the error message you would get:

So.. what exactly is wrong here? It’s definitely impossible to tell from the error message. And this is not an isolated case, I’ve tried error messages like these before with react-redux among other things.

It is a real fear to me, that as the type-system grows in complexity, at some point it will be so complicated as to be useless. If you can’t figure out what the types are telling you, they’re not helping as much as they’re just a gatling gun of incomprehensible error messages.

TypeScript 3.0 has better error messages on the roadmap, so hopefully this is something the team has their eye on.

Ecosystem fragmentation

React Native 0.56 includes this snippet in their changelog

“We’re migrating away from PropTypes and runtime checks and instead relying on Flow. You’ll notice many improvements related to Flow in this release.”

With the several variants of transpile-to-js languages above, I think there’s a real risk of ecosystem fragmentation.

“This library only has TypeScript types. Well? this one can only be used typed if you’re using Flow. But I’m using ReasonML, what should I do?”

I think there’s a lot of duplicate effort currently typing the same libraries for interop between the different dialects of JavaScript. There’s no easy solution to this, as a type-system found in e.g. Kotlin can’t use types from TypeScript out of the box, as the type-system in Kotlin isn’t dynamic enough to understand things like mapped types.

I think it makes sense for the good of the ecosystem, to consider whether we need some sort of standard type-format, just like we have with source-maps. It’s probably not going to be as complex as the TypeScript typings, but that’s probably also fine - most libraries don’t have typings that complex anyway,

I think it’d be a tragedy if we ended up in different walled, typed gardens though.

Boundary type-checking

One of the stated goals non-goals of TypeScript is this:

“Add or rely on run-time type information in programs, or emit different code based on the results of the type system. Instead, encourage programming patterns that do not require run-time metadata.”

I think this has both pros and cons. For the most part - this is fine. There’s a few places where you’d want to use type information inside your app, dependency injection probably being the biggest. However this is solved in things like Angular and InversifyJS through using the experimental emitDecoratorMetaData flag.

However, the big one where this would really help is with type-checking at the boundaries of your app. In most typed languages, you’re able to express that you’re accepting a request with an object that has X shape.

In TypeScript, you can of course do the same - but as the type-information does nothing at run-time, there’s no way to ensure that the type you say you’re expecting is actually the one you get.

If you care about the structure of the object, you’re going to need to specify it at run-time using something like

class-validators or io-ts,

but this requires you to specify types in a way, that is, in my opinion a lot less elegant than a TypeScript interface.

Now TypeScript is actually doing something in regards to boundary-checking with the new top-type unknown - which is basically a type we know nothing about. You can accept a boundary object with the type unknown - and you’re then forced to at run-time check what type it actually is.

I still think something like a run-time check, ala flow-runtime would make sense for TypeScript. Something like a "validate" keyword or a “validateType()” function that compiled to a function, that ensured that the object was actually the stated type.

Though as this is explicitly against the design-goals, I probably wouldn’t hold my breath for this one - we’ll have to do with unknown for now.

Do you see any other problems typescript is facing, or do you disagree with some of these? Reach out at @GeeWengel

Did you enjoy this post? Please share it!